MDMA: Roadmaps to Regulation – Executive Summary

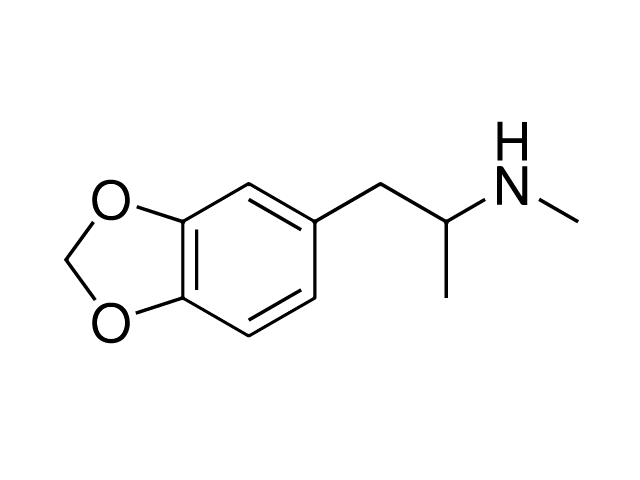

MDMA is well established as a popular psychoactive substance across much of the Western world. Hundreds of thousands of people break the law to access its effects, which include increased energy, euphoria, and enhanced sociability. The categorisation of MDMA as a Class A drug in the UK and Schedule I drug internationally – categories reserved for drugs deemed to pose the highest risk to individuals and society – has never meaningfully disrupted its supply, nor its widespread use. MDMA is cheaper and purer than ever before and is available at the click of a mouse via darknet drug markets.

For several years, MDMA-related adverse events and fatalities have been increasing in the UK, with some claiming that taking MDMA today is the riskiest it has ever been. Responses are polarised between those who assert that the risks of MDMA use necessitate mitigation through prohibition and increased law enforcement, and those who perceive prohibition to be exacerbating these risks by exposing users to an unregulated market of pills and powder of unknown strength and quality. Whichever view you take, current policy is not meeting its goal of reducing harms, and greater control of MDMA production, distribution, purchase, and consumption is needed in order to prevent MDMA-related emergencies.

This report examines the acute, sub-acute, and chronic harms related to MDMA use in detail. We examine the production, distribution, purchase, and consumption of the drug; related risks and harms; and the impact prohibition has on these, as well as the potential impact of alternative policies. Crucially, our evidence shows that most harms associated with MDMA use arise from its unregulated status as an illegal drug, and that any risks inherent to MDMA could be more effectively mitigated within a legally regulated market.

Under prohibition, people purchase MDMA pills, crystal, and powder from an illegal market, with little certainty as to what these contain. Given that illegal drugs are not subject to strict production standards, consumers are exposed to the risks of poisoning or accidental overdose as a result of contamination, adulteration, and unknown strength and purity. Naïve commentators demonise the drug and simply urge young people to ‘just say no’, whilst failing to account for those who say ‘yes’. In the meantime, preventable deaths continue to occur, and otherwise law-abiding people are punished for non-violent offences such as the possession or social supply of MDMA. Governments and the mainstream media persist in perpetuating the myth that the War on Drugs is winnable if it were fought harder, and those calling for drug policy reform – as we do here – are framed as ‘radicals’ who have little or no regard for the health and wellbeing of citizens.

This characterisation could not be further from the truth. Those calling for careful reform to existing drug policy include the parents of young people whose lives have been lost or ruined by harms related to the prohibition of MDMA. We incorporate their voices in this report alongside those of academics and former police officers, highlighting the ‘broad church’ of those dedicated to fighting for reform. This includes scientists undertaking ground-breaking research into the therapeutic potential of MDMA, who work within a regulatory regime that makes such research exorbitantly expensive and time-consuming, because of the Schedule 1 status that MDMA holds in the UK.

As we enter the fourth decade of MDMA’s widespread use, new thinking is needed on how to better control production and distribution, and on how to reduce the risks associated with its consumption. There is growing evidence to support reorienting drug policy away from an ideologically driven criminal justice-led model to one rooted in pragmatic health and harm reduction principles. This is reflected in the widespread reform of cannabis laws occurring in numerous jurisdictions around the world, and the growth of treatment programmes for heroin users which include prescription heroin and supervised injecting rooms. These hard-fought policy changes acknowledge the failure of prohibition to meet its goals and produce a ‘drug-free world’. They are built on a robust and ever-growing evidence base which demonstrates how permitting or prescribing the use of legally regulated drugs improves health and safety outcomes for people who use drugs and their communities at a reduced cost to the state, whilst also providing wider employment and economic opportunities. This logic can be extended to the use of MDMA and other currently prohibited psychoactive substances.

Roadmaps to Regulation: MDMA follows this pragmatic path and pursues policy aims which many of us share, such as improvements in public health promotion, targeted harm reduction, evidence-informed policy and practice, human rights, social justice, participatory democracy, and effective governmental expenditure. For the first time, we outline detailed recommendations for drug policy reform to better control the production, distribution, purchase, and consumption of MDMA products. Reform and the reduction in MDMA-related harms this will bring cannot happen overnight. The changes we outline here, which culminate in a strictly regulated legal market for MDMA, are to be phased in gradually and closely evaluated through independent policy research to ensure health and social outcomes are properly documented, with findings folded back into the ongoing reform process.

Podcast

- All

Links

- All

Support

- All

BIPRP

- All

Science Talk

- All

Amanda's Talks

- All

- Video Talk

- Featured

- 2016 Onwards

- 2011-2015

- 2010 and Earlier

- Science Talk

- Policy Talk

One-pager

- All

Music

- All

Amanda Feilding

- All

Events

- All

Highlights

- All

Psilocybin for Depression

- All

Current

- All

Category

- All

- Science

- Policy

- Culture

Substance/Method

- All

- Opiates

- Novel Psychoactive Substances

- Meditation

- Trepanation

- LSD

- Psilocybin

- Cannabis/cannabinoids

- Ayahuasca/DMT

- Coca/Cocaine

- MDMA

Collaboration

- All

- Beckley/Brazil Research Programme

- Beckley/Maastricht Research Programme

- Exeter University

- ICEERS

- Beckley/Sant Pau Research Programme

- University College London

- New York University

- Cardiff University

- Madrid Computense University

- Ethnobotanicals Research Programme

- Freiburg University

- Medical Office for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Solothurn

- Beckley/Sechenov Institute Research programme

- Hannover Medical School

- Beckley/Imperial Research Programme

- King's College London

- Johns Hopkins University

Clinical Application

- All

- Depression

- Addictions

- Anxiety

- Psychosis

- PTSD

- Cancer

- Cluster Headaches

Policy Focus

- All

- Policy Reports

- Advisory Work

- Seminar Series

- Advocacy/Campaigns

Type of publication

- All

- Original research

- Report

- Review

- Opinion/Correspondence

- Book

- Book chapter

- Conference abstract

- Petition/campaign

Search type