Is microdosing just placebo? Insights from the Beckley Foundation’s research programme

It’s increasingly clear that we’re in the midst of a Psychedelic Renaissance. The past decade has seen a gamut of incredible new research into psychedelic compounds, much of which has been initiated by Amanda Feidling and carried out in collaboration with the Beckley Foundation. We’ve seen evidence that psilocybin can be used to treat depression and addiction, which last year led to the legalisation of psilocybin therapy in the American state of Oregon and a surge in interest from businesses eager to get involved. In 2016, we revealed the first ever images of the brain on LSD, helping us understand the underlying neurology of the psychedelic state, and we’ve been able to form new theories into the nature of the psychedelic experience and its implications for human consciousness and health.

Much of the literature has, until recently, focused on full doses of psychedelics. However, over the last few years, one of Amanda Feilding and the Beckley Foundation’s primary endeavours has been to develop new microdosing research programmes in order to evaluate a practice that has started to receive a great deal of attention, and has opened up the possibility of a different, more widely accessible, and less taboo use of psychedelics.

Microdosing has started to attract mainstream media attention from people curious to know whether it works or not

Amanda has been convinced of the value of microdosing since before psychedelics were made illegal in the 1960s:

“I was introduced to LSD in 1965. In the years that followed, other than the mystical, or peak experience, my aim was to hit that ‘sweet spot’, where vitality and creativity are enhanced, while leaving me in control of my concentration. I grew to love this state. It was, in a way, comparable to what people are doing today with microdosing.”

Determined to subject it to rigorous scientific testing, she set up international research programmes in order to investigate its pharmacology and potential benefits for health and wellbeing. Recently, these research programmes have borne fruit. Two separate Beckley collaborations – the Beckley/Maastricht and Beckley/Imperial Research Programmes – have released findings. The latter study, released earlier this week, constitutes an important early step forwards towards rigorously conducted citizen science, but will need further refinement in order to fully address the question at hand: Does microdosing really have beneficial effects or is it all placebo?

We will address the advantages of both approaches, as well as their limitations, and explain why, in our opinion, the ‘placebo question’ remains largely unresolved.

What is microdosing?

One of the remarkable things about LSD is the tiny doses at which it has its effects – A recreational dose of LSD is generally between 100 and 200μg (1μg is one millionth of a gram) or 0.1 – 0.2 mg. Compare that to, for example, an SSRI anti-depressant like Citalopram, a tablet of which typically contains between 10 – 40mg, or to the ubiquitous painkiller Aspirin, which typically comes in 300mg tablets, and you can see the vast differences. When one considers the powerful effects brought on by LSD – from giddiness and euphoria to hallucinations and ego-death, the tiny quantities required are truly astonishing. In fact, in spite of frequent claims on behalf of challengers, this makes LSD the most potent psychedelic known to man, and a firm challenger to the title of most potent drug overall!

Amanda Feilding first experimented with microdosing in the 1960s

A microdose, however, is even smaller – typically around 1/10th of the quantity of a regular dose, so between 10 and 20μg of LSD, which is a mind-bogglingly small amount of drug. Despite this being too low to cause the kinds of powerful alterations of consciousness typically associated with classic psychedelics, users report all kinds of beneficial effects, such as improvements to wellbeing, mood, social skills, focus, creativity, and productivity.

In addition to anecdotal reports, evidence from numerous observational studies has also indicated beneficial effects, ranging from enhanced mood, creativity and mindfulness, to reduced depression and anxiety. However, until now these studies have lacked the rigorous placebo-controlled approach that ordinarily only lab-based studies would allow.

How does microdosing affect mood and cognition? A lab-based double-blind, placebo-controlled study

At the forefront of modern microdosing research is the Beckley/Maastricht Microdosing Research Programme in the Netherlands, co-directed by Amanda Feilding and Prof Jan Ramaekers, which last year completed its first LSD dose-finding study. Using the gold standard of drug research, a double blind placebo controlled trial, 24 participants were each given a placebo, 5, 10, and 20μg of LSD in a random order, separated by at least five days to ensure any drug from the previous session had been eliminated from the body.

Recent highlights from this study include the first placebo-controlled demonstration of the analgesic effects of low doses of LSD, as well as findings that microdosing increases blood levels of BDNF, a protein implicated in the growth and differentiation of new neurons and synapses.

In terms of mood and cognition, selective, beneficial effects were most apparent following 20μg doses, which is at the upper limit of what is generally considered a microdose. Specifically, at this dose, participants reported increased positive mood, vigour and friendliness compared to placebo. In addition, according to a test that measured the number of attentional lapses in a virtual task, this dose also enhanced sustained attention, perhaps lending credence to anecdotal reports of increased focus and more frequent flow states. On the flipside, subjects also reported increased confusion and anxiety, which tended to be felt during the ‘come-up’ and ‘come-down’, respectively. These negative effects are in accordance with previous reports and are often seen at more conventional doses as well.

One limitation of this and other previous microdosing studies is that they may not adequately reflect the ‘real life’ effects of microdosing. At higher doses, it’s broadly accepted that the effects of psychedelics can’t be separated from the set and setting in which they’re being taken. If microdoses also rely on internal mindset and external environment, it’s possible that a full day in a lab with a battery of cognitive tests and questionnaires doesn’t produce cognitive effects that accurately reflect the day-to-day experience of microdosers.

However, when it’s illegal to produce, possess or distribute your chosen object of study, carrying out official research comes with its challenges. In the UK, for example, LSD and psilocybin are Schedule 1, Class A drugs, which means they’re officially considered to have no medical use and come tangled up in a legal web of strict regulations and penalties. In practical terms, this means that researchers are faced with stacks of paperwork and mounting bills before they can actually get to work.

A Novel, Self-Blinding Approach

Participants followed given instructions in order to prepare their own microdosing capsules, then followed a schedule that determined which days to take them

With these challenges in mind, Drs Balazs Szigeti and David Erritzoe of Imperial College London, and Amanda Feilding of the Beckley Foundation, collaborated on the development of an innovative, naturalistic study design in order to investigate the practice of microdosing in ‘real life’, with a sizeable number of subjects, and for a fraction of the cost of a lab-based study. This constitutes an important early step forwards towards rigorously conducted citizen science, is the first ever psychedelic study to use placebo control outside of the lab, and was completed by 191 participants, making it by far the largest placebo-controlled psychedelic study to date.

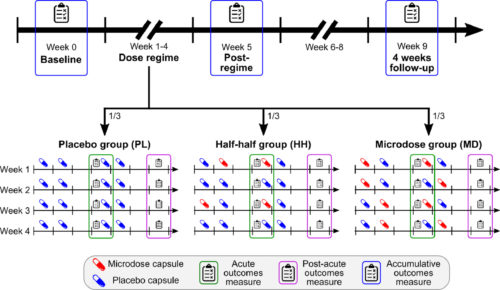

Participants around the world who were already microdosing or planning to do so in the future were recruited online and asked to prepare opaque capsules containing either a microdose of their preferred psychedelic, or a placebo, i.e. nothing at all. Importantly, participants provided their own drug, keeping bureaucratic escape artistry and its resultant costs and delays to a minimum.

After preparing the capsules, participants placed each of them inside an envelope labelled with an individual QR code for later tracking, and then dosed themselves in accordance with one of three randomly assigned schedules, taking placebo, microdoses, or a bit of both.

Participants either took 4 weeks of placebo (PL), 4 weeks of microdoses (MD) or 2 weeks of placebo and 2 weeks of microdose (HH) (Szigeti et al, 2020)

The average active dose consumed was reported as being around 13μg, give or take 5μg or so, which, according to our previous findings at Maastricht University, is enough to cause some effects, but below the 20μg dose recommended by that research. Psychological tests were carried out in order to examine well-being, mindfulness, life satisfaction and – to check previously reported negative side-effects – neuroticism and paranoia.

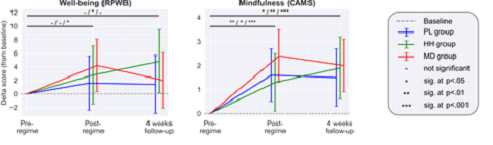

When tested shortly after dosing, scores on microdosing days were generally higher than on placebo days, and when the full four weeks were up, those who had microdosed for the duration reported improved psychological outcomes across the board compared to their baseline tests – greater sense of wellbeing, increased mindfulness and more life satisfaction, alongside decreased paranoia and neuroticism. Significant changes were also seen in the placebo group for mindfulness and paranoia, but not for the other measures.

Therefore, it’s important to note that reports in the media that there were improvements in both the placebo and microdosing groups are only part of the whole picture.

“Finally!”, cry the microdosers, “Bust out the blotters! We’ve got the data!”

Microdosing led to lasting improvements to mindfulness, and some improvement to wellbeing. Dashes and asterisks at the top of the graphs represent degree of significance for placebo / half-half/ microdosing, respectively (Szigeti et al., 2020)

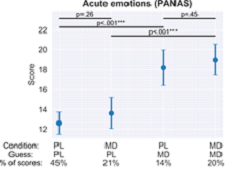

Well, maybe not. The scale of the changes to well-being induced by the microdoses, while significant, was relatively small. In addition, on dosing days and at the end of each week, participants were asked to guess whether they thought they’d taken a microdose or a placebo. When this guess was accounted for in the statistical analysis, it transpired that participants’ belief that they had received a microdose was a greater predictor of positive effects than whether or not they had actually received anything, even for those who were on placebo. This suggests that believing one has taken a microdose generates expectations which lead to perceived benefits.

Szigeti et al (2020): The lines at the top of each graph show that guessing one has taken a microdose (longer lines) is a more significant predictor of changes to emotion than actually taking one (shorter lines). The same was true for mood, anxiety, and depression. No significant changes were observed for cognitive performance in any condition.

Szigeti et al (2020): The lines at the top of each graph show that guessing one has taken a microdose (longer lines) is a more significant predictor of changes to emotion than actually taking one (shorter lines). The same was true for mood, anxiety, and depression. No significant changes were observed for cognitive performance in any condition.

Full figure available here.

Throwing the baby out with the bathwater?

Positive results may need to be taken with a microdose of sodium chloride, then, but there are some considerations that should be taken into account when examining these findings.

Firstly, we must consider what caused participants to ‘break the blind’, or become aware of the nature of their capsule. When participants were asked what factors made them suspect they had taken a microdose, 27% indicated that it was wholly due to body or perceptual sensations such as muscle tension or altered perception of colour, compared to 4% due to mental or psychological effects only. In other words, side effects unrelated to the measures being tested caused people to break the blind and conclude they were taking a microdose.

As the team at Maastricht observed, at doses of 10 or 20μg, participants feel ‘a good drug effect’, ‘high’ or ‘under the influence’, which is likely enough for subjects to be able to break the blind. This clearly indicates that while psychedelic microdoses are often referred to as sub-perceptual, a more accurate term would be sub-hallucinogenic. At doses high enough to have an effect on mood, microdosers should be able to identify what they’ve taken, and we saw this in the Imperial study: Guess accuracy was greater than would be expected if participants chose randomly, and this was mostly due to superior identification of the microdose, rather than the placebo.

Future research should make use of some kind of mildly psychoactive substance – an ‘active placebo’ – with similar physical side effects, in order to make it more difficult to tell the two conditions apart.

It’s also important to note that separating participants into separate groups based on their guesses in this way is not commonplace. If this were done when testing the efficacy of other drugs, whether they be analgesics or antidepressants, it’s very likely that the placebo effect would be more prominent in these cases as well. Indeed, research into antidepressants has been accused of this very oversight, which ignores blind-breaking and could inflate their reported efficacy. It is a credit to the researchers involved that microdosing is being put through this more rigorous testing, but directly comparing microdosed psychedelics to other drugs or treatments that have not undergone this thorough analysis would perhaps be unfair.

Easy dose it

The Beckley/Maastricht study demonstrated that subjective experiences of drug effects are strongly linked to the size of the dose ingested. As participants in the Imperial study provided and prepared their own substances, presumably sourced from their usual supplier, there was not only variation in which drug people chose to use, depending on individual preference and availability, but there was also no guarantee of the doses of compound in each microdose. The average reported dose was 13μg, but without laboratory testing, there’s no way of confirming this number. Responses from microdosers in previous studies suggested that up to 67% of respondents don’t know the dose they consume. Even if the reported dose in this case is accurate, the standard deviation around this average was 5μg, which, when we’re dealing with such low doses, could be the difference between an effect and a lack thereof.

Our findings from Maastricht University indicate that a 10μg dose is perhaps too small for most people to feel a beneficial effect. However, significant improvements were observed following 20μg. It’s certainly possible that the doses consumed by participants in the self-blinding Imperial study simply weren’t high enough to produce changes dramatic enough to comprehensively outperform placebo.

It’s worth repeating that the self-blinding did find that microdosing had greater effects than placebo, but that guesses were a greater predictor of psychological effects than the true nature of the capsule. This might be because guesses more accurately separated low, ‘subthreshold’ microdoses from higher, ‘active’ ones.

Nonspecific Amplifiers

Further complicating matters is the manner in which psychedelics might interact directly with the placebo effect itself, or its underlying causes. Stanislav Grof, a psychiatrist and early advocate of psychedelic therapy, referred to psychedelics as ‘nonspecific amplifiers’, and this ties in with the concept of ‘set’ and ‘setting’.

We accept that the nature and outcome of a psychedelic experience is inextricably linked with the mental state, cultural context, and external environment in which it takes place. Psychedelics increase suggestibility, improving the efficacy of conventional therapy. This is not an undesirable side effect, but is key to their action.

“The purpose of the therapist in the preparation of the psychedelic-assisted psychotherapeutic experience, is to optimise the self-hypnosis of the participant towards a positive outcome, by the concentration on the ‘intention’.

This recognises the advantage of increased neuroplasticity brought about by the ingestion of a psychedelic compound.”

– Amanda Feilding

Some participants went through 4 weeks of placebo, and yet were convinced that they’d been microdosing the whole time. As one participant reported, “I was indeed taking placebos throughout the trial. I’m quite astonished […] It seems I was able to generate a powerful ‘altered consciousness’ experience based only on the expectation around the possibility of a microdose.” It is the power of self-hypnosis, combined with intention, which can cause an empty capsule to produce a profoundly altered state of consciousness. Of course, nobody wants to take part in a month-long psychedelic trial and take placebo the whole time, so there may also have been a certain element of wish-fulfilment here.

In order to truly unpick the contributions of the placebo effect on the outcome, some genuine deception might help – telling all participants that they’re taking a psychedelic, when in actuality, only some are. Ultimately, the best approach might consist of an initial evaluation of pre-microdosing personality traits that might predispose them to the placebo effect, such as openness and suggestibility, in order to weigh their data against this measure. This is already being done in some drug trials, involving a preliminary assessment period in which all participants receive only a placebo, allowing exclusion of those subjects found to be highly responsive to the placebo effect.

Know Thyself: When the observer becomes the observed

One finding that may be important here is a reported increase in mindfulness. While it would be easy to explain this merely as a consequence of the microdosing itself, it may be something else.

While attempts were made to replicate real-world microdosing regimes in which participants take their dose and go about their day, the careful preparation of capsules, adherence to the dosing schedule, and the self-introspection required to complete the psychological measures may have led to increased expectation and placebo effects, or to positive outcomes associated with regular mindfulness. With the study lasting for more than a month, perhaps even those receiving placebo were benefitting from this unintentional dose of self-awareness. The fact that increased ratings of mindfulness were seen in the placebo group as well, before accounting for guess, would appear to support this theory.

Placebo or not?

While it may be tempting to conclude in favour of the findings of one study or the other, the fact is that for the time being, the queston remains unanswered, and it’s likely that there is some element of truth in both. We may not find that some of the more remarkable claims for microdosing are backed up by evidence, but when there are decades of evidence of beneficial effects, more research must be conducted, and future studies will need to improve upon the limitations identified here.

While solving the problems associated with the placebo control methodology might represent a real puzzle in itself, particularly in the realm of subjective psychological effects, another more reliable approach may be to look at non-subjective physiological markers of drug effects.

As previously mentioned, the Beckley/Maastricht microdosing study was able to measure dose-related increases in levels of BDNF in participants’ blood following LSD microdoses, indicating that there are ‘real’, non-subjective changes brought about by microdosing that are not the result of placebo. BDNF is a marker of neuroplasticity, and appears to be an important contributor to the therapeutic efficacy of ketamine in the treatment of major depression.

While the self-blinding study undoubtedly overcame some of the many challenges facing microdosing researchers, such as the high cost of the compounds, and of the participants’ time in the lab, plus the regulatory hurdles involved in lab-based studies, there is still a long way left to go before such studies are entirely satisfactory, as there remains serious doubt regarding the quality and quantity of the compounds taken.

Looking to the future

With that in mind, the Beckley Foundation is aiming to conduct more research in this area.

In particular, Amanda Feilding is working with various institutions to examine the effects of microdosing in individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions, for whom the effects of microdosing may be greater. Previous research, including the studies discussed above, have mainly focused on healthy individuals.

We are working on the development of a remote research platform that will leverage mobile technology via apps and the rapidly growing capacity to securely collect data through connected devices, with the goal of allowing research participants to perform surveys and assessments on their own, without having to physically visit a scientific laboratory or clinic. This is particularly important as COVID-19 and ongoing measures to combat its spread have provided further reason to take a step back from lab-based studies. This approach could offer many advantages, such as having access to a much greater number of participants, considerably reducing the cost of research, and learning from individuals’ existing experience and knowledge of these compounds. However, limitations may need to be accounted for in the future.

Meanwhile, the team at the Beckley/Imperial Microdosing Research Programme aim to begin Phase 2 of their Self-Blinding Microdosing Study in the second half of this year. This will be the very first study to look at the cumulative effects of microdosing, over a period of 3-5 months, and will also build on the findings of the Beckley/Maastricht Programme by testing how this might affect levels of BDNF.

If you’d like to support this and help us discover more about microdosing, in order to finally put the ‘placebo question’ to bed, you can donate to the Beckley Foundation here.

Jon Sharp

Sources

Hutten, N., Mason, N. L., Dolder, P. C., & Kuypers, K. (2019). Motives and Side-Effects of Microdosing With Psychedelics Among Users. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol, 22(7), 426–434.

Hutten, N., Mason, L., Dolder, P.C., Theunissen, L., Holze, F., Liechti, M.E. Feilding, A., Ramaekers, J.G., Kuypers, K. (2020). Mood and cognition after administration of low LSD doses in healthy volunteers: A placebo controlled dose-effect finding study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 41(41), 81-91.

Johnstad, P.F. (2018). Powerful substances in tiny amounts: An interview study of psychedelic microdosing. Nordic studies on alcohol and drugs, 35(1), 39-51.

Kirsh, I. (2014) Antidepressants and the Placebo Effect. Z Psychol, 222(3)

Sonawalla, S.B., Rosenbaum, J.F. (2002) Placebo response in depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci, 4(1): 105-113

Szigeti, B., Blemings, A., Kaertner, L., Rosas, F., Feilding, F., Nutt, D., Carhart-Harris, C., Erritzoe, D. (2020). Is it just placebo? Exploration of psychedelic microdosing using novel self-blinding methodology.

.

Podcast

- All

Links

- All

Support

- All

BIPRP

- All

Science Talk

- All

Amanda's Talks

- All

- Video Talk

- Featured

- 2016 Onwards

- 2011-2015

- 2010 and Earlier

- Science Talk

- Policy Talk

One-pager

- All

Music

- All

Amanda Feilding

- All

Events

- All

Highlights

- All

Psilocybin for Depression

- All

Current

- All

Category

- All

- Science

- Policy

- Culture

Substance/Method

- All

- Opiates

- Novel Psychoactive Substances

- Meditation

- Trepanation

- LSD

- Psilocybin

- Cannabis/cannabinoids

- Ayahuasca/DMT

- Coca/Cocaine

- MDMA

Collaboration

- All

- Beckley/Brazil Research Programme

- Beckley/Maastricht Research Programme

- Exeter University

- ICEERS

- Beckley/Sant Pau Research Programme

- University College London

- New York University

- Cardiff University

- Madrid Computense University

- Ethnobotanicals Research Programme

- Freiburg University

- Medical Office for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Solothurn

- Beckley/Sechenov Institute Research programme

- Hannover Medical School

- Beckley/Imperial Research Programme

- King's College London

- Johns Hopkins University

Clinical Application

- All

- Depression

- Addictions

- Anxiety

- Psychosis

- PTSD

- Cancer

- Cluster Headaches

Policy Focus

- All

- Policy Reports

- Advisory Work

- Seminar Series

- Advocacy/Campaigns

Type of publication

- All

- Original research

- Report

- Review

- Opinion/Correspondence

- Book

- Book chapter

- Conference abstract

- Petition/campaign

Search type