Lessons from Portugal: The Case for Drug Policy Reform

In 1999, a hundred thousand people in Portugal – nearly 1 % of the total population – were addicted to heroin. Fuelled in part by risky practices like syringe sharing among those who injected drugs, the country reported the highest rate of drug-related AIDS deaths in the European Union.

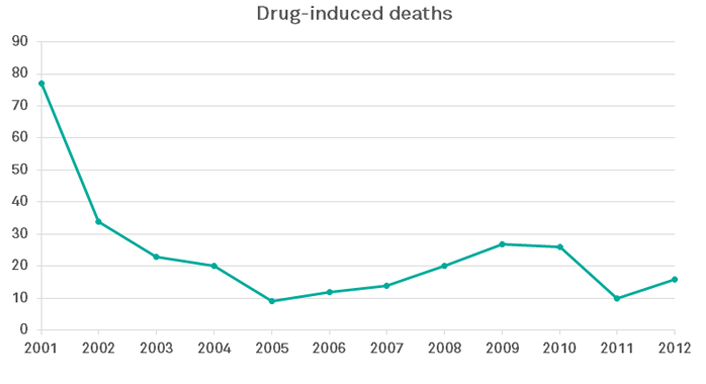

Today, the Health Ministry estimates that about 25,000 people in Portugal are users of heroin, and the drug mortality rate is the lowest in Western Europe: 1/10 the rate of Britain taken as a whole, 1/27 the rate of Scotland, and about 1/50 the rate of the US.

Portugal, it seems, is winning the war on drugs. And it is doing so by not fighting it. In 2001, a progressive government moved to shift the focus of its drug policy to prioritise treatment over penalisation, generating a major public health campaign to tackle addiction, while simultaneously decriminalising the possession and use of all drugs- from cannabis and psychedelics, through to cocaine and heroin.

Rate of drug-related deaths in Portugal following decriminalisation, courtesy of Transform Drugs

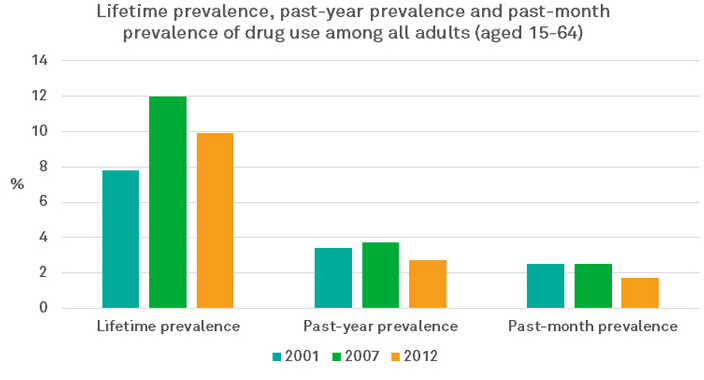

Opponents warned that the move would lead to a rampant increase in drug use and addiction. It did not. Opponents warned that Portugal would become a haven for ‘drugs tourism’. It did not. They warned that drug-related crime – drug sales, theft, and prostitution – would increase. It did not.

Instead, the most reliable measures of drug use have decreased, drug-related deaths have decreased, and problem drug users who want to quit can feel confident about seeking the help they need without incriminating themselves: those on probation, for example, can access support without having to first admit to an offence. As a result, the numbers entering treatment for addiction are higher than ever. Surely these are the metrics by which the success of a drug policy should be judged.

Prevalence of drug use in Portugal since decriminalisation, courtesy of Transform Drugs

Over the same period of time, successive UK governments have continued to pursue policy that puts moralising over morality, privileges criminality over vulnerability, and insists – beyond all evidence to the contrary – that we can arrest and stigmatise our way out of this problem. For three consecutive years, drug-related deaths in the UK have increased, hitting record numbers, and the Cumbrian town of Barrow-in-Furness (population 60,000) is on track to suffer as many opioid-related deaths this year as the entirety of Portugal (population 10,000,000).

The severity of drug law enforcement in a jurisdiction has little, if any, discernible effect on rates of drug-taking. This is not a controversial claim: a Home Office report under the coalition government came to this conclusion, as did several reports before it. And yet, the prohibitionist mindset continues, fixated on decreasing the prevalence of drug use at all costs, and thereby exacerbating – if not directly causing – many of the risks and harms that policy purportedly aims to counter.

By the Home Secretary’s own admission, the illegality of the drugs market means that rival suppliers settle their differences with violence. With no regulatory oversight, drug users have no idea what they are taking and risk consuming adulterated drugs, rat poison, or deadly fentanyl. And among the most vulnerable populations, problematic drug users feel unable to seek the help they need for addiction. It is incumbent on us to put harm-reduction at the centre of our drugs policy, beginning with the decriminalisation of personal possession.

The tragic case of 15-year-old Leah Kerry, whose inquest last week confirmed a drug-related death, serves as a reminder that the lethal consequences of drug policy are not restricted to the most marginalised among us, but can be borne by any sector of society. The desire for consciousness-alteration is universal, and the impulse for risk-taking and experimentation particularly strong among teenagers. The illegality of the pills that contributed to her death did nothing to stop Leah and her friends – or the hundreds of thousands of other young adults in the UK who take ecstasy – being able to purchase and consume them. But the illegality did mean that there was no dosage or purity testing in the production of the pills to minimise their risk profile. It meant that a 15-year-old was able to acquire the drugs, where a supermarket would have turned her away from purchasing alcohol. And it meant that her friends hesitated in securing emergency help for Leah, fearful of the repercussions.

Beckley Foundation Director Amanda Feilding with President Otto Perez Molina of Guatemala (2012-5)

Amanda Feilding set up the Beckley Foundation in 1998 to address the issue of drug prohibition, and to put an end to the devastating collateral damage to health, life, and human rights caused by the war on drugs. Her ground-breaking seminar series ‘Society and Drugs: A Rational Perspective’, hosted at the House of Lords, brought together politicians, scientists, and policy analysts in one of the first attempts to develop a hard evidence base for policy reform, leading to the formation of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Drug Policy Reform, the International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC), and the International Society for the Study of Drug Policy (ISSDP). The 2011 Beckley Foundation Public Letter, calling on world governments to try a new approach to drug policy, was signed by Presidents, UN High Commissioners, and Nobel Laureates. Since then, Amanda has served as an advisor to several governments including those of of Guatemala and Jamaica, helping to guide the reform of their drugs laws to prioritise harm-reduction.

Later this year, the Beckley Foundation will release Roadmaps to Regulation, a series of four reports assessing the benefits and harms of different regulatory models for cannabis, psychedelics, MDMA, and new psychoactive substances, reflecting on how we might reduce the harms of drug use associated with the status quo. By demonstrating how policy reform could be enacted across a range of contexts, the reports will have global applicability.

Calls for decriminalisation can no longer be considered expression of a fringe view. The UK government’s own Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, as well as the Royal Society for Public Health, and three consecutive UN Secretary Generals, have all called for the decriminalisation of drug use. The British Medical Association also supports prioritising treatment over criminal justice, offering a range of evidence-based interventions for managing illicit drug use, to align illicit drug policy with tobacco and alcohol strategies: doing so will provide a set of common principles for addressing addiction and substance misuse. The evidence from Portugal could not be clearer: criminalising drug users neither decreases drug use nor encourages people with addiction into treatment. So why continue?

Words: Eddie Jacobs

Podcast

- All

Links

- All

Support

- All

BIPRP

- All

Science Talk

- All

Amanda's Talks

- All

- Video Talk

- Featured

- 2016 Onwards

- 2011-2015

- 2010 and Earlier

- Science Talk

- Policy Talk

One-pager

- All

Music

- All

Amanda Feilding

- All

Events

- All

Highlights

- All

Psilocybin for Depression

- All

Current

- All

Category

- All

- Science

- Policy

- Culture

Substance/Method

- All

- Opiates

- Novel Psychoactive Substances

- Meditation

- Trepanation

- LSD

- Psilocybin

- Cannabis/cannabinoids

- Ayahuasca/DMT

- Coca/Cocaine

- MDMA

Collaboration

- All

- Beckley/Brazil Research Programme

- Beckley/Maastricht Research Programme

- Exeter University

- ICEERS

- Beckley/Sant Pau Research Programme

- University College London

- New York University

- Cardiff University

- Madrid Computense University

- Ethnobotanicals Research Programme

- Freiburg University

- Medical Office for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Solothurn

- Beckley/Sechenov Institute Research programme

- Hannover Medical School

- Beckley/Imperial Research Programme

- King's College London

- Johns Hopkins University

Clinical Application

- All

- Depression

- Addictions

- Anxiety

- Psychosis

- PTSD

- Cancer

- Cluster Headaches

Policy Focus

- All

- Policy Reports

- Advisory Work

- Seminar Series

- Advocacy/Campaigns

Type of publication

- All

- Original research

- Report

- Review

- Opinion/Correspondence

- Book

- Book chapter

- Conference abstract

- Petition/campaign

Search type