OUT OF UNGASS: Thinking Ahead of the Outcome Document at the Beckley Foundation Side Event

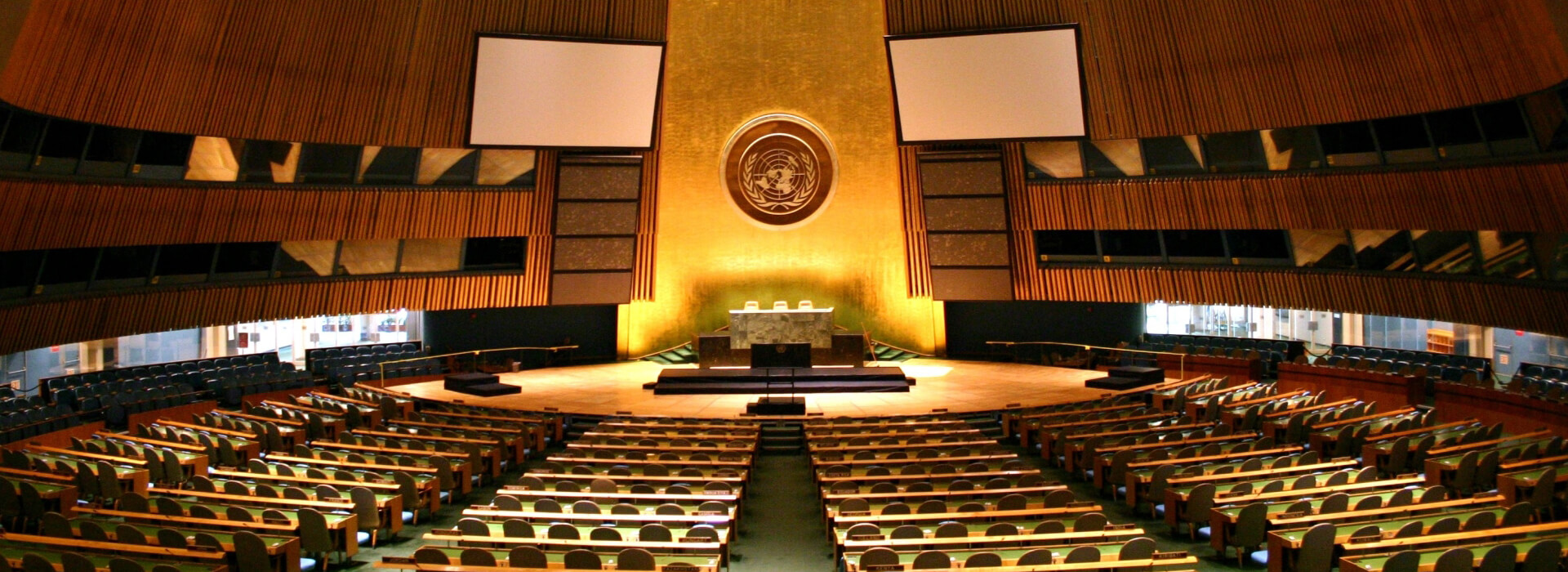

Amanda Feilding recently led a Beckley Foundation delegation to the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Drugs (UNGASS), comprising a diverse range of civil society members including Harvard law professor Charles Nesson, former Jamaican Justice Minister Mark Golding and President of the Westmoreland Hemp & Ganja Farmers Association.

With the delegation, Amanda officially launched the 2016 Public Letter of the Beckley Foundation at the UN Headquarters in New York on April 21st at the climax of UNGASS. The Public Letter affirms that fifty-five years after the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs was launched, it is clearly evident that the global war on drugs has had many unintended and devastating consequences worldwide, and has failed to eliminate drug production or drug use. It is a call to action for respect of human rights and national sovereignty, and for universal access to medication and the sanctioning of scientific research.

The Public Letter opens with a reminder that “[r]espect for human rights and national sovereignty are founding principles of the UN.” Correspondingly, Ras Iyah-V opened his discourse by deconstructing the UN Declaration of Human Rights, exposing the undeniable contrast between the document’s platitudinous ideation of a world where “human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want” and the realities engendered by the ‘war on drugs.’ Iyah-V noted that a lot of “lip service” had been paid to Declaration over the course of UNGASS. The Declaration claims to shun “barbarous acts,” committed in “contempt of human rights,” when, in fact, these terms accurately describe his first-hand experiences of UN drug policies over the decades, emblematic of Jamaica’s powerlessness to withstand the dictates of the United States.

“Sovereign states have the right to form and implement domestic drug policies that their governments consider best for their own citizens.” Senator Mark Golding addressed the disappointment felt keenly by the entirety of the reformist contingent of UNGASS, with regard to the Outcome Document and at the fact that the General Assembly itself has adopted what he described as “a conservative position.” He explained that one country on its own- especially a small country such as Antigua or Santa Lucia- “does not have the strength to row its own canoe in choppy waters” against the current of more powerful countries. For Golding, out of UNGASS, a sense of clarity was born: if we are to achieve global drug policy reform, increased cohesion is needed between all nations that seek it, rich and poor. By 2019, he suggests, many of the demands made by the Beckley Foundation’s Public Letter in 2016 will have been met, as drug policies begin to catch up with evolved, and internationally integrated, attitudes.

“Certain plants and substances are currently listed on Schedule I of the UN Single Convention despite having medical potential and not being highly addictive, and despite having been used by indigenous people for millennia.” The cost to medicine is felt worldwide; Armando Loizaga Pazzi, the Mexican advocate of the rights of the indigenous people of South and Central America described a kind of “pharmacological colonialism” whereby indigenous groups “ravaged by Crystal Meth” are plied with anti-depressants and other manufactured pills, put are prohibited from using natural plants with psychoactive properties in the treatment of their addictions.

The Public Letter calls for these plants and substances to “be moved from Schedule I to Schedule II, thereby opening the doors to research and allowing physicians to prescribe them where appropriate.” This suggestion was met with warmth by Dr Ben Sessa, a psychiatrist, researcher and Beckley Foundation collaborator. Sessa and others bore witness to a “strangle-hold” currently being placed on developing clinical research into psychedelics because of the scheduling of these drugs. Cannabis, MDMA, LSD and psilocybin all have therapeutic applications, but the UK Home Office “put every barrier in the way that they can,” rendering it extremely difficult to demonstrate this by bringing them into the clinical arena.

Amanda Feilding has launched the 2016 Public Letter of the Beckley Foundation at a time when global drug policy remains disappointingly ripe for reform. Nevertheless, as demonstrated by its reception, attitudes are aligning internationally to enable this long-awaited improvement.

Podcast

- All

Links

- All

Support

- All

BIPRP

- All

Science Talk

- All

Amanda's Talks

- All

- Video Talk

- Featured

- 2016 Onwards

- 2011-2015

- 2010 and Earlier

- Science Talk

- Policy Talk

One-pager

- All

Music

- All

Amanda Feilding

- All

Events

- All

Highlights

- All

Psilocybin for Depression

- All

Current

- All

Category

- All

- Science

- Policy

- Culture

Substance/Method

- All

- Opiates

- Novel Psychoactive Substances

- Meditation

- Trepanation

- LSD

- Psilocybin

- Cannabis/cannabinoids

- Ayahuasca/DMT

- Coca/Cocaine

- MDMA

Collaboration

- All

- Beckley/Brazil Research Programme

- Beckley/Maastricht Research Programme

- Exeter University

- ICEERS

- Beckley/Sant Pau Research Programme

- University College London

- New York University

- Cardiff University

- Madrid Computense University

- Ethnobotanicals Research Programme

- Freiburg University

- Medical Office for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Solothurn

- Beckley/Sechenov Institute Research programme

- Hannover Medical School

- Beckley/Imperial Research Programme

- King's College London

- Johns Hopkins University

Clinical Application

- All

- Depression

- Addictions

- Anxiety

- Psychosis

- PTSD

- Cancer

- Cluster Headaches

Policy Focus

- All

- Policy Reports

- Advisory Work

- Seminar Series

- Advocacy/Campaigns

Type of publication

- All

- Original research

- Report

- Review

- Opinion/Correspondence

- Book

- Book chapter

- Conference abstract

- Petition/campaign

Search type