Oiling the Hinges of the Doors of Perception – Microdosing with Psychedelics

As the psychedelic renaissance advances, and ever more clinical studies begin, we are coming to understand just how crucial to healing the peak psychedelic state is: that most profound shift in conscious experience, where patients experience a sense of unity with all things, a transcendence of time and space, the dissolution of the ego itself, alongside profoundly positive emotions of joy, connection, and love. In this state, the doors of perception are well and truly opened, and these experiences can be indistinguishable from those described across various mystical traditions. However, as psychedelics can fairly regularly engender these experiences in people regardless of their religious or spiritual beliefs, many researchers prefer more the secular term of ‘peak experience’ to ‘mystical experience’.

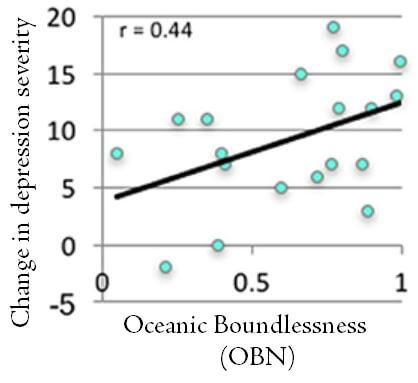

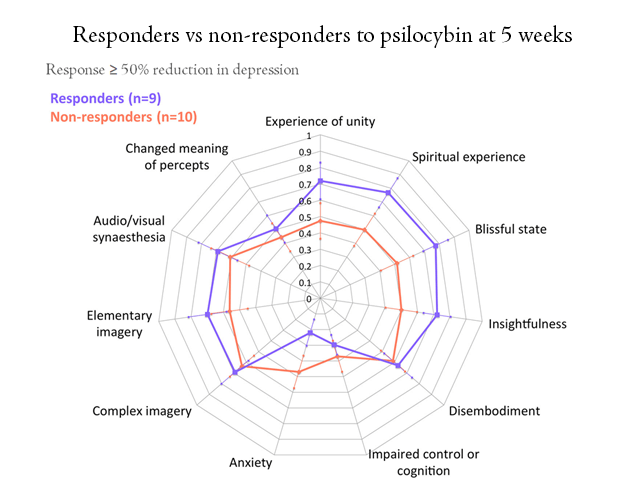

Across a number of studies, including those undertaken as part of the Beckley/Imperial Psychedelic Research Programme, we have found that the quality of the peak (or mystical) experience predicts how successful a psychedelic treatment is. In our ground-breaking investigation of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression, we found that those patients who healed the most had, during the psilocybin sessions, experienced the greatest feelings of oceanic boundlessness, a dissolution of the boundaries of the self associated with heightened mood, sublime happiness and serenity. While the academic community comes to recognise these out-of-the-ordinary experiences as highly valuable for development and healing, it is precisely because of them that many people are uneasy about engaging with psychedelics as a treatment.

How much patients experienced oceanic boundlessness predicted the extent of their relief from depressive symptoms.

Valuable as these states are for healing, it would be wrong to say that they are indispensable. A study released earlier this year found that a single dose of LSD reduced excessive alcohol consumption in mice, and very few people would suggest that the mice underwent mystical experiences. The practice of microdosing, taking small doses of psychedelics regularly, rather than large doses infrequently, has now attracted a huge number of advocates, especially in the tech and creative industries. More palatable to the wider community than large doses, microdosing does not involve any ego-dissolving mystical-type experience, and yet anecdotal reports of myriad benefits, including significant antidepressant effects, abound. The ability of LSD to provide an anti–depressant effect, without the mystical, classically psychedelic component, suggests that there is much more to be learned about its underlying mechanisms of action.

In our study of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression, the patients who had the most intense, mystical-like experiences, went on to have the greatest reductions in severity of symptoms.

.

Regular dosing of LSD has long been an interest of mine: back in the 1960s, before the prohibition of psychedelics, I carefully experimented with regular doses. In those days, apart from occasions of the peak experience, my aim was to find that ‘sweet spot’, where vitality and creativity are enhanced, while leaving me in full control of my behaviour. Smaller, regular doses of psychedelics truly can act as a ‘psychovitamin’, enriching lives in all manner of ways. Microdosers are not, as some might portray them, breaking the law in order to get high. A properly sized microdose – typically 1/10th the size of a standard recreational dose – produces no changes to perception, or hallucinogenic effects, whatsoever. Microdosers are breaking the law in order to be sober, but ‘improved’. Reading through accounts of the experiences of microdosers, a theme that appears again and again is that these small amounts of LSD allow the user to work better and with more enthusiasm and focus, think more creatively, and feel more alive to the present moment—what we might today call “living mindfully.” They also report an improvement in mood, with many microdosers using the practice to alleviate from their depression.

Microdosers of LSD will tend to take just a fraction of a tab to achieve the desired effects. More than 10-30 micrograms can lead to alterations to visual perception, which most people prefer to avoid during the working day Image: BBC News

In spite of an increasing number of microdosers oiling the hinges to the doors of perception, all of the current evidence on the practice is anecdotal in nature. There are still no placebo-controlled scientific studies exploring the mechanisms of action, benefits, or possible side-effects of microdosing. The discoverer of LSD himself, my friend the sadly departed (at the age of 102) Albert Hofmann, declared that microdosing is the most under-researched aspect of psychedelics. That remains true to this day. And now, precisely because of the increasing number of adherents, rigorous scientific research is all the more urgent.

Since finally succeeding in carrying out the first brain imaging study with LSD in 2016, I have been wanting to extend our LSD research to include the microdosing phenomenon. Now, with Beckley Foundation collaborators Professor Jan Ramaekers and Dr Kim Kuypers at the University of Maastricht, we are carrying out a study assessing the physiological and psychological impact of various sized microdoses. Across the space of a month, participants are receiving different sized microdoses, and their effects on creativity, cognitive flexibility, mood and well-being are being assessed. Moreover, we are collecting much needed data about vital signs to establish the safety profile of the practice, as well as taking blood to measure markers of neuronal growth and neuroplasticity, another promising potential application of LSD.

I am also formally about to start a much needed lab study into microdosing using EEG to measure changes in connectivity and neuroplasticity. This study is to be placebo controlled.

As part of the Beckley/Imperial Psychedelic Research Programme, we have recently launched this new study in which people from all over the world can participate remotely. There have been a number of naturalistic studies of microdosing before, which, although valuable contributions to the literature, share one key shortcoming: participants, taking their own drugs, know that they are microdosing. With this in mind, it’s difficult to rule out the placebo effect: perhaps, after all the hype over microdosing, people are experiencing and reporting benefits merely because they believe they will experience them. Our new study, by using an entirely novel, self-blinding protocol, will ensure that participants are unaware of which days they are taking a microdose, and which days they take placebos. At the end of a month, we will unblind participants, sending them a personalised report, detailing which days they were microdosing. We can correlate their daily performance scores with which days they were microdosing, and participants can know with confidence how the practice affects them in reality.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FDmOBEJYO8I[/youtube]

The study is now recruiting. If you are already microdosing, or about to start, you can make a tangible, important difference to psychedelic science by joining the study. By collecting data from hundreds of microdosers, we can advance our understanding of the potential benefits of low doses of psychedelics.

We have so much still to learn about the microdosing experience, and I hope our studies will cast more light into the shadows, and that we will soon have a better understanding of how microdosing can benefit mental health, creativity, and well-being more generally.

Microdosing may well be the ideal way to rehabilitate psychedelic compounds in the eyes of the world: a pill that enhances energy, vitality, creativity, and mood, while allowing the user to retain full control of their focus and behaviour, could be a welcome addition to our current pharmacopeia in the midst of a rising tide of mental health disorders.

As Francis Crick wrote in his diary: Suppose a psychedelic chemical was produced to make people more intelligent, with no addictive properties or bad side effects would you object to it?

Amanda Feilding

Podcast

- All

Links

- All

Support

- All

BIPRP

- All

Science Talk

- All

Amanda's Talks

- All

- Video Talk

- Featured

- 2016 Onwards

- 2011-2015

- 2010 and Earlier

- Science Talk

- Policy Talk

One-pager

- All

Music

- All

Amanda Feilding

- All

Events

- All

Highlights

- All

Psilocybin for Depression

- All

Current

- All

Category

- All

- Science

- Policy

- Culture

Substance/Method

- All

- Opiates

- Novel Psychoactive Substances

- Meditation

- Trepanation

- LSD

- Psilocybin

- Cannabis/cannabinoids

- Ayahuasca/DMT

- Coca/Cocaine

- MDMA

Collaboration

- All

- Beckley/Brazil Research Programme

- Beckley/Maastricht Research Programme

- Exeter University

- ICEERS

- Beckley/Sant Pau Research Programme

- University College London

- New York University

- Cardiff University

- Madrid Computense University

- Ethnobotanicals Research Programme

- Freiburg University

- Medical Office for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Solothurn

- Beckley/Sechenov Institute Research programme

- Hannover Medical School

- Beckley/Imperial Research Programme

- King's College London

- Johns Hopkins University

Clinical Application

- All

- Depression

- Addictions

- Anxiety

- Psychosis

- PTSD

- Cancer

- Cluster Headaches

Policy Focus

- All

- Policy Reports

- Advisory Work

- Seminar Series

- Advocacy/Campaigns

Type of publication

- All

- Original research

- Report

- Review

- Opinion/Correspondence

- Book

- Book chapter

- Conference abstract

- Petition/campaign

Search type